Nutrition of premature babies: challenges and solutions

Nutrition of preterm infants is a major concern worldwide, especially in Africa, where preterm birth rates are high. According to the WHO, approximately 15 million babies are born preterm each year. Preterm birth rates vary from 5% to 18% between countries. In Africa, over 60% of preterm births occur in Africa and South Asia. The Comoros, Equatorial Guinea, Mozambique, Gabon, Mauritania, Congo, Zimbabwe, and Malawi are among the African countries with the highest prematurity rates.

Preterm infants are babies born before 37 weeks of gestation. A full-term pregnancy is considered to be 41 weeks of amenorrhea. Preterm births face many health and growth challenges. Several stages of prematurity are distinguished by gestational age:

- Before 28 weeks: extremely preterm

- Between 28th and 32nd week: very preterm

- Between 32nd and 37th week: moderate to late prematurity

Preterm infants have specific and higher nutritional needs than full-term infants because they did not have time to fully develop in the womb. The first months of life are therefore crucial for their survival and development. In this article, we will examine the challenges of preterm infant nutrition in Africa and solutions to address them.

Before Nutrition, Critical Care Conditions for Survival

Preterm infant survival chances are strongly linked to the birth environment. In low-income countries (in Africa and South Asia), half of infants born at 32 weeks or less do not survive. This is due to the lack of equipment to recreate a mother’s womb-like environment—especially warmth—so the preterm infant can continue to grow. Added to this are nutritional difficulties, respiratory challenges, and infection care issues. In high-income countries with advanced medical technology support, survival rates are near 100%.

Preterm Infants’ Nutritional Needs

Preterm infant nutrition is crucial. In Africa, where prematurity prevalence is high and healthcare infrastructure is often limited, it is even more critical.

To survive and continue normal development, a preterm infant needs adequate nutrition that provides the same nutrients as if still in the womb, ensuring normal clinical evolution and long-term neurodevelopmental prognosis.

Therefore (editor’s note):

- Provide enough energy to meet expenditures and avoid catabolism (the metabolic phase of breaking down organic compounds with energy release and waste elimination)

- Provide sufficient amino acids to achieve positive nitrogen balance and protein synthesis

- Supply water and electrolytes in adequate amounts to support physiological adaptation from fetal to postnatal life, while maintaining homeostasis (the system’s ability to maintain its internal balance despite external changes)

- Ensure nutrition minimizes and prevents metabolic disorders associated with prematurity

- Optimize nutritional intake to promote growth and development

To achieve this, two principles are generally implemented and proposed to parents: optimize early parenteral nutrition and introduce adequate enteral nutrition (via a tube to the stomach or small intestine) as soon as possible.

Breast Milk: Top Recommendation for Premature Infants

Breast milk is the best milk for any baby, preterm or not. This is especially true for preterm infants who need tailored nutrition for full-term growth, impacting first survival and then healthy development.

A study from Toulouse University Hospital showed that breast milk versus formula affected IQ in preterm children: those fed breast milk had higher IQs at study’s end. Moreover, breast milk composition meets preterm infants’ nutritional needs, reducing risks of cognitive deficits at ages 2 and 5, decreasing necrotizing enterocolitis, lowering infections and hospital stays—overall improving long-term prognosis.

Mothers of preterm infants may face difficulties breastfeeding due to insufficient milk production or other challenges. In such cases, they can be encouraged to express milk for administration via nasogastric tube (enteral route) or by cup feeding.

Parenteral Nutrition

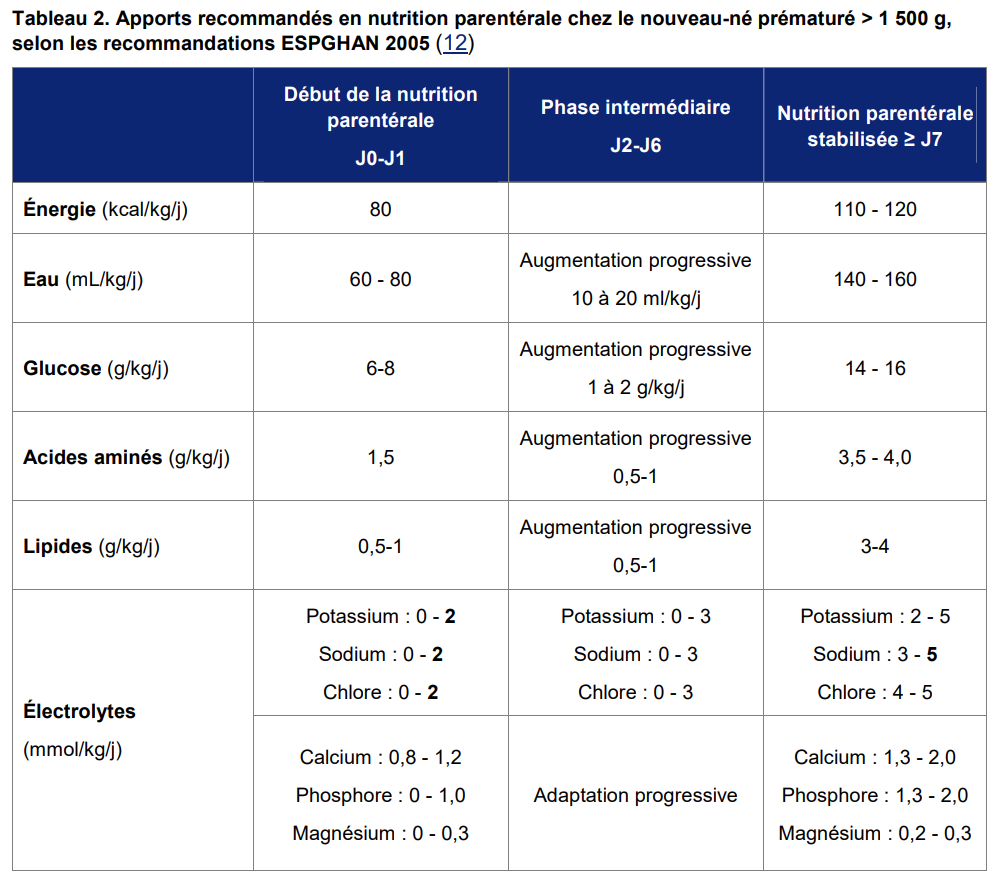

Parenteral nutrition involves administering a complete nutrient mix—macronutrients (glucose, amino acids, lipids), electrolytes, and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals)—via central intravenous line. It is used when enteral feeding is impossible, insufficient, or contraindicated. This applies in initial complications like respiratory distress syndrome, patent ductus arteriosus, hemodynamic instability, or immature intestine seen in extremely preterm infants. It is generally administered to preterm infants or children who cannot be fully fed orally or enterally.

A physician in neonatal, neonatal intensive care, or pediatric intensive care units prescribes parenteral nutrition.

Three Types of Nutrient Bags

Nutrient bags come in three types, with supply methods varying accordingly.

First, bags with marketing authorization (MA) purchased from an industrial manufacturer. These are adapted for newborns, infants, children, and adolescents, and usually require supplementation with other nutrients based on the child’s needs.

Next, standardized bags are produced by the hospital’s pharmacy department (PUI) or outsourced. They are used more generically, varying by institution, and aimed at general patient populations.

Finally, custom bags are formulated for individual children based on specific needs and administered exclusively to them.

Prescription responsibility lies with physicians. These prescriptions are tailored to the medical diagnosis and the nutritional, metabolic, and medical needs of each child.

Early parenteral nutrition administration reduced the time to regain birth weight by 2.2 days in preterm infants.

Although widely used, parenteral nutrition requires caution due to risks such as catheter-related infections or electrolyte imbalances. Therefore, only experienced healthcare professionals should administer it, and infants must be monitored to detect any complications.

Challenges to Improving Preterm Nutrition in Africa

Preterm infant nutrition in Africa faces many challenges, including:

Limited Healthcare Access

Healthcare is often inaccessible in rural and remote areas of Africa, making it difficult for parents of preterm infants to obtain necessary medical care. Lack of access also prevents parents from getting the guidance and information needed to properly feed their baby. Beyond remoteness, even major African cities face issues: a scandal at the Nkongsamba regional hospital in Cameroon, where a preterm infant died in an incubator fire.

Thus, the first obstacle to these babies’ survival is the quality of infrastructure and essential services like electricity and running water.

Poverty

Poverty is another major barrier to preterm nutrition in Africa. Often, families must purchase their own medications and bring them to the hospital. Poor families often cannot afford nutritious foods for their baby, leading to malnutrition and health issues. Preterm nutritional support also continues after hospital discharge; at home, a regimen must be followed to help reach a physiological state similar to that of a term infant.

Lack of Breast Milk

Breast milk is the best food for preterm infants because it contains essential nutrients for growth and development. However, many mothers struggle to produce enough breast milk due to malnutrition and stress. Preterm infants who cannot receive sufficient breast milk are often fed with formula substitutes, which can be expensive and hard to source.

Infectious Diseases

Preterm infants are more vulnerable to infectious diseases than full-term infants. In Africa, where infectious disease rates are high, preterm infants are particularly exposed, affecting their ability to absorb nutrients and grow normally.

Solutions for Preterm Nutrition in Africa

Although preterm infant nutrition in Africa faces challenges, solutions exist to help ensure adequate feeding. Possible solutions include:

Promote Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding is the best nutrition source for preterm infants. Mothers should be encouraged to breastfeed as soon as possible. Health facilities can support breastfeeding by providing information on donor human milk and assisting with milk expression: reducing stress, using breast pumps, and encouraging at least eight expressions per 24 hours (including nighttime) to reach 500 ml by day 10, plus breast massage.

Provide Nutritious Foods

When breast milk is insufficient, it is important to provide nutritious alternatives. Health facilities can supply infant formula or fortified milk to ensure babies receive necessary nutrients.

Educate Parents on Preterm Nutrition

Parent education on preterm nutrition is essential for ensuring adequate feeding. Health facilities can provide guidance on feeding techniques and recommended foods for optimal growth and development.

Improve Healthcare Access

Improving healthcare access is vital to ensure preterm infants receive necessary medical care. Providing proper equipment to health facilities, regardless of location, is paramount.

Prevent Infectious Diseases

Preventing infectious diseases is important to protect preterm infants’ health. Vaccines and medications should be made available as needed to ensure protection against infections.

In summary, preterm infant nutrition in Africa is a crucial health challenge requiring focused action. By promoting breastfeeding, providing nutritious alternatives, educating parents, improving healthcare access, and preventing infections, we can help ensure preterm infants receive the nutrition and care they need for optimal growth and development.

Each preterm infant is a blessing deserving the best start in life, beginning with adequate nutrition and proper medical care. Health facilities, parents, healthcare professionals, and the community can work together to ensure every preterm infant has access to the support they need for a brighter future.

At SennaCare, we forge partnerships between individuals and healthcare professionals to make quality care accessible to all. Contact us to discuss your needs and receive the best possible assistance.